This week, in light of the intense controversy the slated removal of the city’s Confederate monuments has invoked, I thought I would excerpt a previous post that seems relevant to the discussion, as well as include a few compelling images from past and present.

As anyone who has been paying attention is well aware, the statue of Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, perched between the bayou and the entrance to City Park, is one of the monuments that will be removed in the near future. Given the high emotions surrounding this decision, I couldn’t help but think of the history of this particular intersection—both its political and geological history.

From my previous post about the roiling energy of this particular intersection, with some current commentary woven through:

“Around where the Bayou St. John meets Esplanade Avenue, near the entrance to City Park: this place is its own ‘energetic system’….The phenomena, geological and historical, that have unfolded at this location over the last few thousand years have charged it up so much that next time you’re there—crossing over the bridge to go to the NOMA, for example—you might be able to feel it. [Oh boy, that’s truer today than ever!] Let me give you the briefest of brief histories about this particular spot.

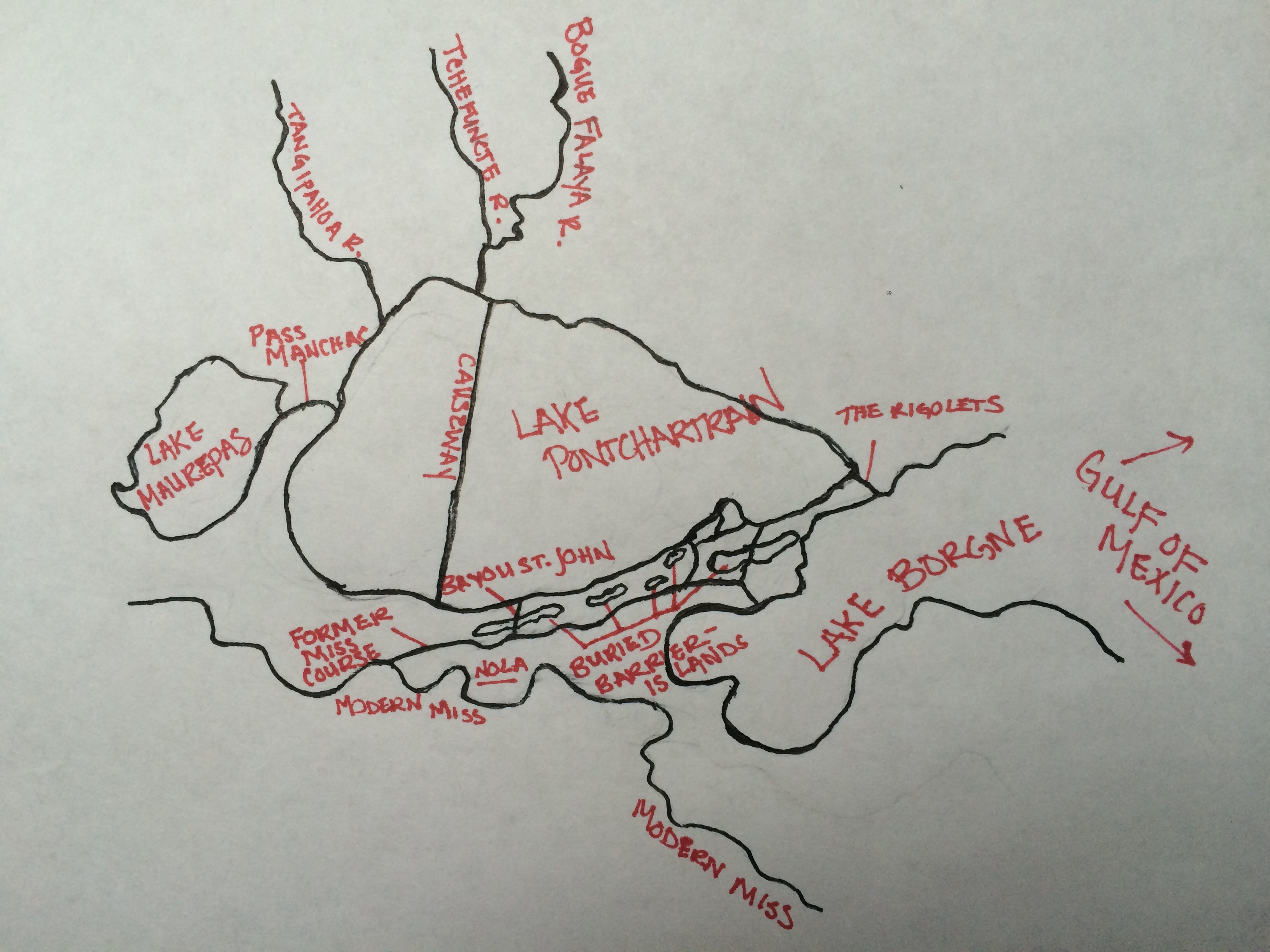

Before the Mississippi River swung toward its current path 700 years ago, a main arm of the river flowed west to east from present-day Kenner, through the heart of New Orleans, out to present-day New Orleans East.

They call this, among other similar names, the Metairie-Sauvage distributary. This former limb of the Mississippi River is crucial to our tale. For one thing, it built up the relatively high, well-drained Metairie-Gentilly ridge system…. It also spawned (gasp!) the bayou itself! Near where modern-day Esplanade Avenue nears City Park, this former distributary meandered…sharply. No one quite knows why it did, but we do know that in the process of meandering it sent yet another distributary southward (a body of water simply called the Unknown Bayou, that would eventually form Esplanade Ridge) and another, smaller distributary northward, toward the lake (the Bayou St. John!). For some inexplicable reason, the Metairie-Sauvage distributary split into three, irregular fingers at this location—and thank goodness it did! [1]

Here’s another theory about the bayou’s birth, since what I’ve explained above is not 100% certain: it’s possible that after the Mississippi chose its current path 700 years ago and the Metairie-Sauvage course was abandoned—becoming a sluggish bayou in the process—the Bayou St. John formed as a drainage conduit for this larger bayou. At a weak point in the natural levee (around where present-day Esplanade nears City Park!) the Metairie-Sauvage flood waters crevassed and flowed toward the lake, a process that would repeat itself until the bayou was gouged permanently into the landscape. It’s possible, indeed probable, that the formation of the bayou is a combination of these theories—a drainage conduit throughout the millennia, if you will.

Either way you slice it, this spot—near where City Park Avenue meets Carrollton at Moss, near the roundabout with P.G.T. Beauregard at its center, near where the bridge spans the bayou and oak-lined Esplanade begins—has seen a lot of prehistoric action. Water trickling, gushing, overflowing, bifurcating—to the north, to the southeast, to the east. Water heaping up and creeping through. It’s seen a lot of historic action as well.…”

Yes, yes it has. And it is watching history unfold as we speak!

postcard courtesy of Bayou St. John resident Bill Abbott

photo by Simi Kang, 2017.

photo by Simi Kang, 2017.

1. Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2008) 77-78.